This Week in Reading

Into the Fire by Hoa Thu

My grandmother spent the last decade and a half of her life working on her memoir, a forever unfinished tome carefully handwritten in Vietnamese. After she died last year, her brother-in-law edited her papers into a single book, which my mom translated into English.

In personal nonfiction, the general rule is that you should not try to come across well. Spare your generosity for everyone else in your life, and leave none for yourself. But my grandmother was not reading Mary Karr or Elizabeth Wurtzel or any of the other confessional writers defining the genre. She was reading Don Quixote. And so instead of portraying herself as a flawed protagonist, she has written herself as the tragic heroine of an epic novel.

To be fair, her life is worthy of an epic tale. Written in the third person with a fictional name, the memoir primarily focuses on the first 26 years of her life. By the time she was my age, she had been imprisoned three separate times and three different men had declared their eternal love to her—each on “the wrong side of the war.” First there was the French captain, Marchadier, who wanted to whisk her away to Hanoi and spoil her with luxuries—but she was too patriotic to accept. Next, my grandfather—her cellmate at the communist detention camp whose fate she accidentally tied herself to via a note she slipped him as he was carted away, assuming he was to be executed. Finally, her one true love, the communist chief who ran the last detention camp she was held at, after she was arrested for being a double agent for both sides. She was shot in the hand and hiked through the muddy river to escape her French occupied village. Her father was a polygamist. At some point she got a translator thrown into prison on false information, which she doesn’t seem remorseful about in the slightest. Into the Fire is essentially the Vietnamese version of Gone with the Wind—one hundred percent drama, one hundred percent of the time. (For her eventual marriage to my grandfather, she reserved three pages of the book. The birth of her five children and their escape to America—the climax of my mother’s life story— was afforded a single paragraph.)

In her telling, she is regal, dignified and sophisticated no matter what situation she is thrust into. Through her alter ego, Liên, she frequently describes herself as a beautiful intellectual. She is constantly translating fragments of French poetry, and being complimented on her intelligence.

“Liên was energetic, vivacious and skilled in entertaining people with her stories. She would get into the middle of a quarrel and deftly settle the dispute. Similar to her previous trips to the North, whenever she met her comrades, men or women, old or young, they all enjoyed her lively talk and gregarious nature.”

Humility? Never heard of her. Coming of age in a generation that venerates self-deprecation, it is almost startling to read someone describe themselves in such unabashedly flattering terms. Instead of forfeiting the power of the author, she weaponizes it. As there are no other tellings of these events to contradict her, we must take her at her word: she was the most beautiful and interesting woman of all time. If history belongs to the victors, the narrative is controlled by those who bothered to write it down.

The way she tells it, she somehow “reigns over the whole camp,” despite being, you know, a prisoner. My favorite anecdote is this one:

“All the prisoners slept on the cold hard floor, with no bedding even in the winter, the only warmth came from body heat. Clothing was sparse and bathing restricted, the place was infested with lice and bed bugs. By morning, the bugs crawled in long lines like black ants. As a delegate, Liên got a room corner to herself. Her helpers lay outside next to her to block the bugs’ path. Bôn with dark eyes and Hiền of honey skin, were two of her most trusted confidants. The girls stayed close to her, brought her water to wash up, brought her food, did her laundry, and swept where she slept.”

Yes, somehow my grandmother—a literal prisoner—convinced the other prisoners to…be…her servants? Whether this assertion is a testament to the magnitude of her power or her self-delusion, the sheer boldness of this recounting demands respect.

Her approach may be the opposite of modern memoirists’, but even the most unflinchingly self-aware writers have the same agenda as my grandmother: to be loved, admired, praised. These memoirists want to be lauded for their transparency and honesty, their ability to tap into the raw power of ugly emotions—but they are still writing for validation, to ensure their legacy as a piercing observer of the world around them. My grandmother’s goals for her legacy are more straightforward: she simply wants to be remembered as staggeringly beautiful and powerful and charming. It’s a different kind of transparency, to be so forthright about how you want your audience to see you.

Into the Fire is different in strategy than the books of Molly Wizenberg or Jeannette Walls, but it reminds me of a newer kind of first person narrative: the celebrity documentary. A documentary about Demi Lovato produced by Demi Lovato has about the same level of objectivity as a memoir written in the third person. The story is removed from the subject by one degree: the declarative “I” replaced with the fictional name “Liên”, Demi’s arc relayed through the detached lens of a documentary director. However, this degree of impartiality is entirely illusionary—the narrative remains tightly within the control of the subject.

The Demi documentary is fascinating in that it aims to depict vulnerability without showing weakness. The backbone of Dancing with the Devil is that Demi is unfailingly Brave. Demi does not make bad decisions; when she relapses it is not a mistake but an opportunity for her to courageously ask for help. Her overdose does not reveal her fragility, but rather her strength in recovery. It is not that Demi is not brave— if anything I applaud the way Dancing With The Devil complicates the neat narratives we use to talk about addiction, but it is notable how unwilling the documentary is to portray her in any other light.

These narratives use trauma as a background, something to be conquered. The messy, the imperfect, have no place here. The obstacles they face: a war, colonialism, heroin, alcoholism, an eating disorder, are dark and terrible things, but their darkness does not cast a shadow on the radiant valiance of our heroines. They are never complicit, never responsible, never damaged in a way that cannot be undone by the end of the page. In these narratives, they experience trauma without being affected by it. These stories are a painting of a woman standing in front of a burning building, a single smear of ash across her face, accentuating her bone structure. Not pictured is the smoke in her lungs, her third degree burns, or the screams she hears as she falls asleep. There is so much left out, but, by god, is she beautiful.

Thank you to everyone who has chosen to financially support me by becoming a paid subscriber. I’ve already blown past my original goal of 79 paid subscribers—I would love to hit 100 by my birthday in June. My next paid subscriber newsletter will be a full drama account of my studio saga, which involves jugglers, a messy civil divorce case, armed guards, and a bunch of absolute dirty liars. It’s a juicy story worthy of a full Cut expose, and I will do my best to do it justice. It will also include a secret ~personal announcement~

You can upgrade your subscription here:

Further Reading:

I’ve fallen down the rabbit hole of celebrity documentaries/memoirs. The Paris Hilton one is free on Netflix and is a must watch (there is a major twist I will not spoil for you). I also cannot stop talking about Open Book by Jessica Simpson, which almost made me CRY in the introduction.

P.S.

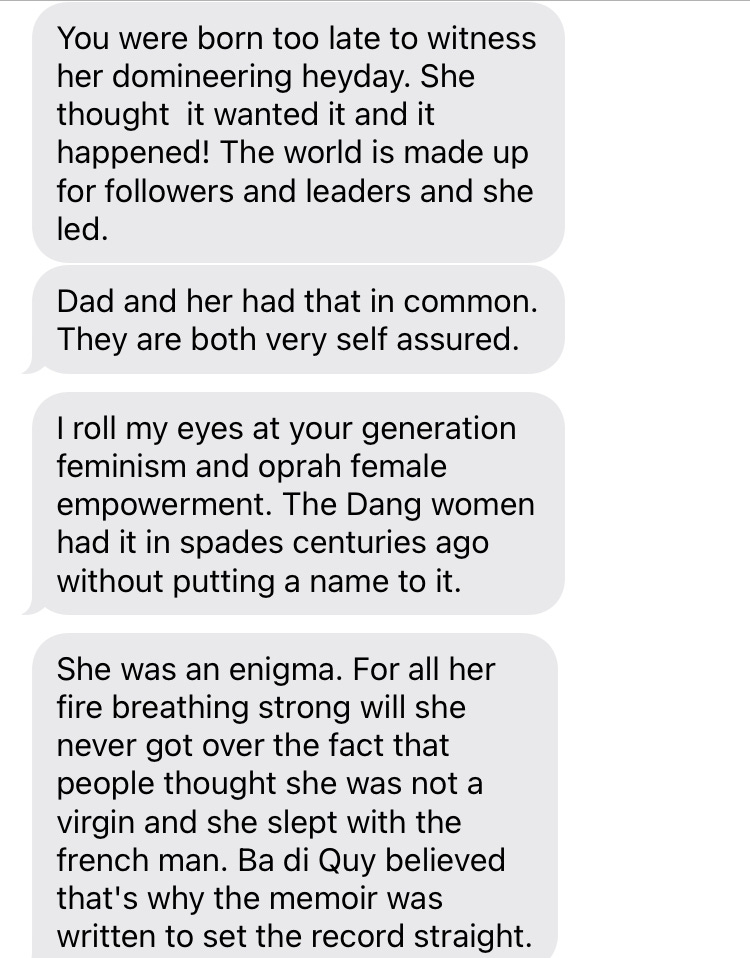

My mother’s review of the memoir: