When people ask why I moved to California I tell them that Los Angeles is a place that disappoints you and so I came here to be disappointed. I thought I would be here for a year or so, but instead I stayed, and then stayed longer. California has disappointed me less than I imagined but has also given me more to think about than I anticipated. To live in Los Angeles is to live in a continuous cycle of myth making and disillusionment.

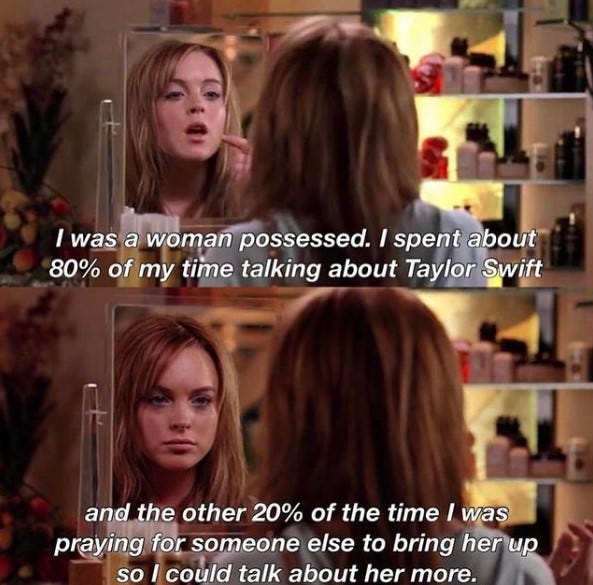

Maybe that is also why I became a Swiftie. It's a kind of masochism– to be a fan in general– but to be a fan of Taylor Alison Swift in particular. Like California, I love her not because she is wonderful, but because I find her baffling, and fascinating, and yes– in moments– glorious. I came for a song, stayed for a lifetime. To be a Swiftie is to buy into a narrative, and then be disappointed, again and again.

Taylor Swift is a product being packaged and sold to us by Taylor Swift. Product Taylor is relatable and goofy. She loves her fans, and her cats, and is so very very clever at turning songs into ciphers. Product Taylor fights for artists’ rights and has big feelings. Maybe Actual Taylor does too– but I’ve never met her.

What the discourse has wrong is that the friction isn’t between Taylor’s public self (generous, good, Glinda-esque) with her secret, true self (evil, conniving); we have no way of knowing Taylor’s private self and never will. That delicious tension we feel is between the public perception of Taylor (ambitious, ruthless, a little shady) and Taylor’s perception of her public self (good, Glinda-esque). I’m a Swiftie because I’m obsessed with the gap between those two realities.

The good, Glinda-Taylor isn’t a lie, necessarily. If anything it is the most potent truth of Taylor– the version of Taylor she believes herself to be. To be a person in the world is to exist as others understand you to be, to be a celebrity is to exist in a million ways in a million minds. But most people would agree that the most important version of self is the one we define for ourselves. Who we imagine ourselves to be, who we aspire to be– is that not the most revealing of our perspective? Is our perspective not who we are?

That said, there has always been more to Taylor Swift than the relatable sweetness she has packaged herself as. After a decade and a half in the public eye Taylor has let her hand slip a little. She has a penchant for revenge, can be petty and spiteful in both her songwriting and her life. She’s a shrewd capitalist and will gladly make a backroom deal to protect her squeaky image and business assets. Her fans and haters disagree about whether these attributes are justified, or even admirable, but any Swiftie with half an eye open will agree that Taylor’s teeth are sharp.

Taylor has always been someone who favors an unambiguous moral narrative– which is why she is a stupendous pop star instead of, say, a contemporary novelist. Like all of us, she contains multitudes– goodness, cruelty, benevolence, spite– but Taylor’s self-narrative is not open-ended enough to account for that complexity. Unable to square Taylor’s contradictions with the unimpeachable product she offered up, her critics call her a hypocrite. Her multiplicity is read as duplicity. And Taylor, a people-pleaser to her core, tries to repackage herself to give them what they want. This past October she dropped “Anti-Hero”:

It’s me, hi, I’m the problem it’s me

It must be exhausting always rooting for the anti hero

After years of people begging Taylor to show any kind of self-responsibility she gave us this alleged anthem of accountability. She’s the problem!!, she sings, over and over. The genius of the song is that it’s actually Taylor at her least accountable, while posturing as her most reflective. “Anti-Hero” is the head cheerleader asking if these jeans make her look fat, fully expecting her friends to jump in and tell her that no, actually, they are a slay, she is fire, etc. It’s a kind of false humility. She says she’s the problem because she wants us to tell her she isn’t. And sure enough, #tayloryoullbefine went viral soon after “Anti-Hero” did, a comforting call and response.

The problem in “Anti-Hero” is not actually Taylor, it is Taylor’s insecurity. Taylor is perfect but she doesn’t know it. She thinks she is a monster on a hill (but she’s not), she thinks she’s bad (but she’s not). She isn’t fighting her own dark humanity, she is fighting the delusion that she, a good, Glinda-esque figure, has a dark humanity at all.

The song does not give space for the possibility that this self-criticism could be rooted in reality. Her flaws have been refracted until they exist almost separately from her. She is only capable of grappling with negative aspects of herself from a great distance—far enough away that she can divorce herself from them entirely when it starts to feel uncomfortable. “Anti-Hero” is a song about how she is worried she is the Bad Taylor everyone says she is— but in writing the song she has outlined Bad Taylor as an entity she can examine at arms length.

She sings, “Did you hear my covert narcissism I disguise as altruism.” Like in Reputation, Taylor is trying to own her criticism—but it’s a false confession. Taylor is not seriously presenting these character flaws for examination. She is still a victim, murdered by her daughter in law for the money. Taylor is writing these songs as repentance, but at her core she believes she was falsely convicted. A more accurate lyric would be: covert innocence disguised as humility.

Taylor can’t help but reach for the most literal possible interpretations for her music videos, and in the Anti-Hero video, Bad Taylor takes the form of a second Taylor who wears sequin hot pants and gives Good (Sad) Taylor shots and teaches her lessons like “Everyone Will Betray You.” It’s a visual device she has been using since the beginning of her career. In “You Belong With Me” in 2009 she plays both the role of the nerdy girl next door (Good Taylor), and the mean, brunette cheer caption she has written herself in opposition to. I think back on this video as the most accidentally self-aware moment of Taylor’s career. The lyrics do not necessitate that she play both roles and yet she has cast herself as both the heroine and the mean girl. It’s Taylor’s carefully curated public self—relatable, dorky, romantic, up against her Shadow Self—attention seeking, vindictive. She is both of them but the audience knows the dorky blonde version of Taylor is the “real” one, the one we should be rooting for. Dark Taylor is just a role she can step into for a moment, before exiting back into the more wholesome, beloved character she is so good at playing.

Taylor is drawn to playing her Shadow Self, but she doesn’t really believe it is a part of her. Taylor Swift is not someone to admit she was wrong, to express regret for a past action. Her life is an unspooling narrative that seamlessly course corrects to protect her image. She wants relatability without paying the price of fallibility, and thus she is performing humanness without offering true humility.

I do not doubt that Taylor’s anxieties are genuine. She is arguably one of the most scrutinized and criticized women in the world and her past experiences with the media and Twitter could be described as a legitimate trauma. But her anguish is not that of failing publicly and being shamed, but rather the anguish of publicly misunderstood. Reputation was her villain era, not because she believes she is the villain, but because she saw herself as an antihero cast as a villain and it felt easier to step into the role than fight against it. Critics and most of the public hated Reputation for the same reason I loved it—it felt inauthentic. Reputation is the student body president smoking a single cigarette. “Look at how bad I’m being! Am I getting an A+ in being bad??” She could not give more fucks about proving she doesn’t give a fuck about her popularity and reputation. It’s off-putting because she comes so short of what she intends, but that is also what is so endearing about it. We are irritated when Taylor’s performed self matches her own idea of herself because that doesn’t match the broader public perception of her. But we are also irritated when she tries to perform the version of her we say she is– the villain, the anti-hero. Which goes to show that the problem was never what version of Taylor is performed but rather the dissonance between what we believe her to be and what Taylor sees herself as. The audience isn’t satisfied controlling Taylor’s image, we want to redefine Taylor’s own understanding of herself, teach her a lesson. She gave us a myth, we excavated our own reality, and now we are trying to rewrite the myth in our image.

“Anti-Hero” is a frustrating song, but in its frustration it manages to capture the full spectrum of Taylor: self-aware while also being completely unaware, trying to give us what we want by only giving what she wants to give. Failing and succeeding to be every version of herself simultaneously– a song falling through a tear in the space-time continuum.

Housekeeping:

Thank you for reading. If you enjoyed this, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription. It’s $5 a month or $50 a year, and it genuinely makes a huge impact in supporting my creative practice.

Last month’s paid subscriber-only newsletter was about the movie Past Lives, the Queer Ultimatum, and Vanderpump Rules. I also send out a monthly digest of five highly curated links that are worth your time.

This month’s paid subscriber-only newsletter will be a guide to hosting, one of my true hobbies.

In other news: Substack recently started a referral program! If you are a paid or free subscriber and get other people to sign up (for a paid OR free subscription), you can get your own paid subscription comped. 3 referrals = 1 month comp, 5 referrals= 3 month comp, 25 referrals= 6 month comp. If you are already a paid subscriber the reward will kick in after your current billing cycle (ie. the next month if you are a monthly subscriber or added on to the end of your year if you are an annual subscriber)

From the archives:

The last time I wrote about Taylor, 5 years ago:

I also did this project about Taylor: “I Have Never Not Thought About Taylor Swift”. I still have posters available if you are interested. $86 including shipping within the US. Just respond to this email if you want to buy one.

I was just telling someone this weekend, “she’s my antihero, but not for the reasons she thinks she is.” ❤️ my petty queen.

I totally agree with your assessment of the superficiality of Antihero, it’s like “self-loathing” *taylor-made* for TikTok. Her most Midnights-y themed song isn’t even on that album, it’s The Archer. Lines like, “I never grew up, it’s getting so old,” or the long “they see right through me, can you see right through me? I see right through me” those feel vulnerable and ring true, but of course we’ll never really know.

I started listening to her after Lover! I constantly question why I am a fan of hers or became a fan. I am always looking for good writing, and in my opinion, she is a skilled writer. She makes certain complex and difficult topics and emotions easy to grasp. “Boys will be boys then. Where are the wise men?” I also like Mean.

I also appreciate that she stands up for other women, including in music. I appreciate her speaking about the sexist archetypes she has broken out of, e.g. being a polite young lady. I hope she continues to speak out about racism. I think she still does not get why Kanye acted the way he did.

Love her or hate her, you cannot ignore the effect she has had on younger artists, music industry, and our culture and society.